America's occupation of Iraq should go on

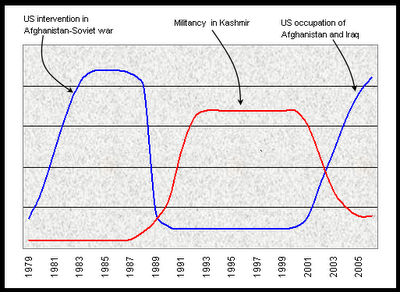

because it is good for India. See graph below to understand why India is gaining from America's loss.

For those who came in late, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979 to support a pro-communist government in Kabul. In reply, America poured millions of dollars through the CIA-ISI pipeline (see Taliban by Ahmed Rashid) to militarily support the Afghan jihad against the Soviets. As part of this strategy, the CIA actively encouraged the recruitment and training of radical Muslims from around the world in Pakistani madrassas to provide manpower to the jihad.

After the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, these well-armed and trained fighters streamed outwards, a good number of them reaching Kashmir. Thus, apart from creating two future nemeses for itself - Osama bin Laden and the Taliban - the US' misfired Afghan policy kickstarted a decade of violence in Kashmir. Foreign jihadis hijacked and overwhelmed the native Kashmiri initiative, and violence remained at a high in Kashmir across the 1990s. The graph showing violence intensities in Afghanistan and Kashmir during that period.

Ironically, 9/11 and the events following it - which brought misery to millions in America, Afghanistan and Iraq - brought succour to Kashmir. As foreign jihadis made a beeline for Afghanistan and Iraq, violence tapered off since 2001 to an extent that Kashmir-watchers now tentatively announce that "normalcy has returned" to Kashmir.

In the US, there is now talk that the failed occupation of Iraq has fanned violence and spawned a whole new generation of radical Muslim militants. Arguably, if the US withdraws and Iraq comes to peace, these unemployed fighters will emigrate to look for greener pastures - likely, back to Kashmir. The US occupation in Iraq provides a much-needed respite for India and a space for political processes to resume in Kashmir; the longer it lasts, the better.

Every time the war-mongers in Washington DC say "Stay the course!", Indians should cheer them on.

Note: Dont ask for references for the figures in the graph, because none exist. Call it BS, but dont miss the point.

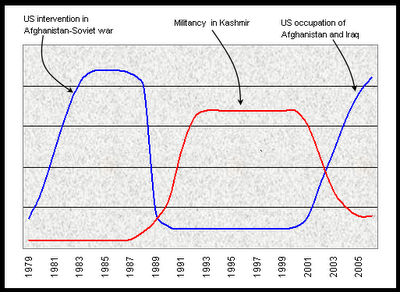

For those who came in late, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979 to support a pro-communist government in Kabul. In reply, America poured millions of dollars through the CIA-ISI pipeline (see Taliban by Ahmed Rashid) to militarily support the Afghan jihad against the Soviets. As part of this strategy, the CIA actively encouraged the recruitment and training of radical Muslims from around the world in Pakistani madrassas to provide manpower to the jihad.

After the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, these well-armed and trained fighters streamed outwards, a good number of them reaching Kashmir. Thus, apart from creating two future nemeses for itself - Osama bin Laden and the Taliban - the US' misfired Afghan policy kickstarted a decade of violence in Kashmir. Foreign jihadis hijacked and overwhelmed the native Kashmiri initiative, and violence remained at a high in Kashmir across the 1990s. The graph showing violence intensities in Afghanistan and Kashmir during that period.

Ironically, 9/11 and the events following it - which brought misery to millions in America, Afghanistan and Iraq - brought succour to Kashmir. As foreign jihadis made a beeline for Afghanistan and Iraq, violence tapered off since 2001 to an extent that Kashmir-watchers now tentatively announce that "normalcy has returned" to Kashmir.

In the US, there is now talk that the failed occupation of Iraq has fanned violence and spawned a whole new generation of radical Muslim militants. Arguably, if the US withdraws and Iraq comes to peace, these unemployed fighters will emigrate to look for greener pastures - likely, back to Kashmir. The US occupation in Iraq provides a much-needed respite for India and a space for political processes to resume in Kashmir; the longer it lasts, the better.

Every time the war-mongers in Washington DC say "Stay the course!", Indians should cheer them on.

Note: Dont ask for references for the figures in the graph, because none exist. Call it BS, but dont miss the point.